You've likely seen this acronym on the side of a service truck and wondered to yourself, "What's HVAC mean?" It sounds ultra-important, and it is: HVAC stands for heating, ventilation and air conditioning, which are systems used to manage indoor climate and air quality.

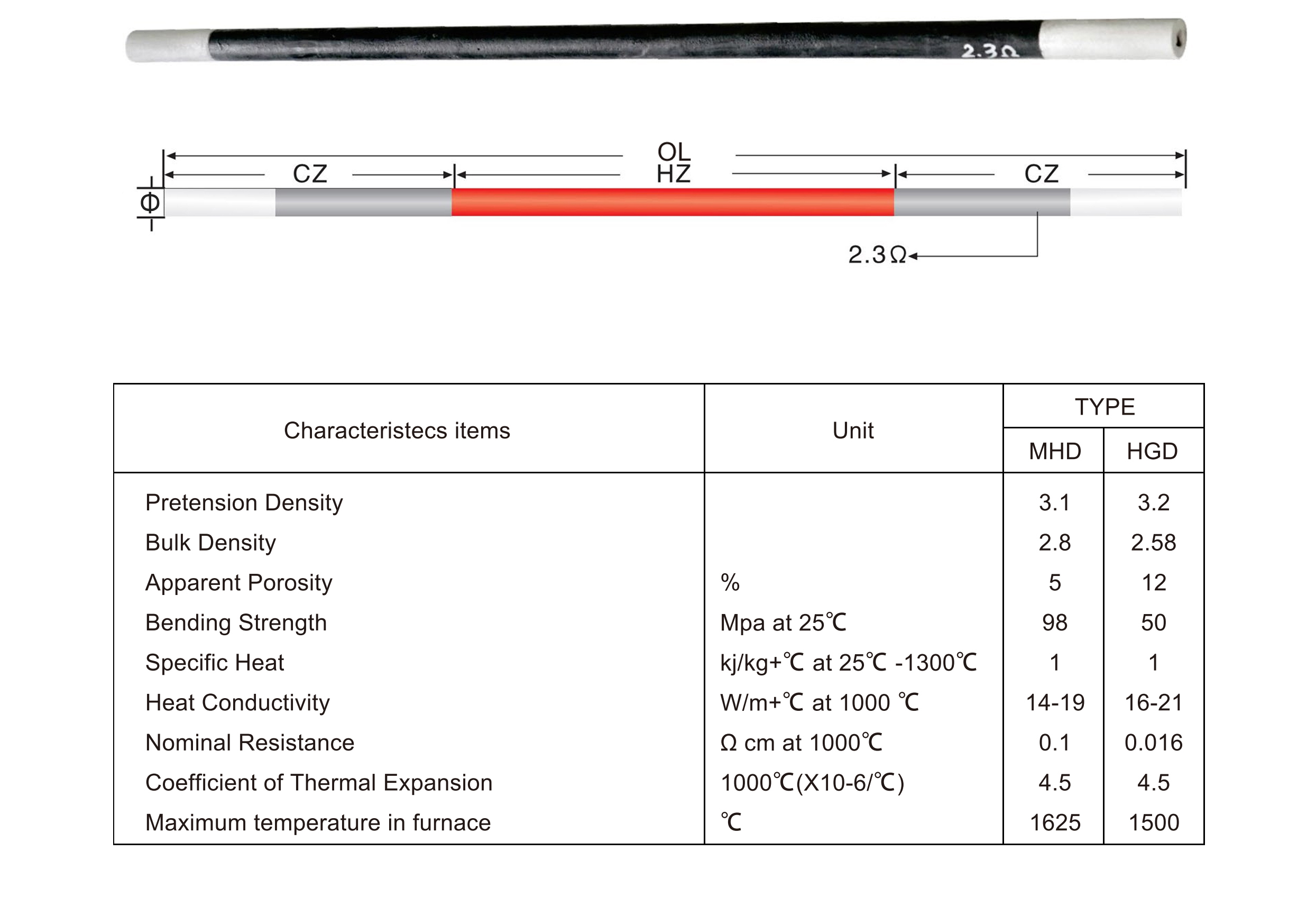

We expect our heating systems to keep us warm during the winter, and we depend on air-conditioning to keep us cool during the summer. Double Spiral Silicon Carbide Heating Element

But most of us have no idea how these systems work. What's the difference between heat pumps and a heat exchanger? What the heck is an air handler? Understanding how the heating and cooling systems function in your home will help you head off problems before they become too serious.

A heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system, or HVAC, is a comprehensive solution for regulating the environmental comfort in buildings and vehicles. Its primary purpose is to provide indoor climate control, ensuring optimal temperature, airflow and air quality.

The heating component is responsible for raising the temperature inside the building during colder months. This is typically achieved through furnaces or boilers, which heat air or water respectively, and distribute the warmth throughout the space via ductwork or radiators.

Ventilation is crucial for maintaining indoor air quality. It involves the exchange of indoor air with outdoor air, removing moisture, odors, smoke, heat, dust, airborne bacteria and carbon dioxide and replenishing oxygen.

Ventilation can be achieved through mechanical means, like fans and ducts, or through natural methods, such as windows and vents.

Air conditioning, often the most recognized part of HVAC systems, cools indoor air during warmer periods. It works by removing heat and humidity from inside the building and releasing it outside, using a system of coils filled with a refrigerant.

Modern HVAC systems are designed for efficiency and can include air filters, humidifiers and dehumidifiers to further refine the indoor environment.

Climate control systems in homes and buildings, like heating and air conditioning, consist of three essential parts: a source for warming or cooling air, a method to distribute this air and a control mechanism — like a thermostat — to regulate the system.

Typically, the same systems distribute and control both warm air from furnaces and cool air from air-conditioning units. For example, in houses with central air conditioning, the cool air often travels through the same ducts used for heating and is regulated by the same thermostat.

The basic principle behind both heating and cooling is the movement of heat from a warmer to a cooler area. Furnaces and heaters add heat to the air to warm your home, while air conditioners remove heat to cool it down.

Different energy sources fuel these systems: Air conditioners typically use electricity, while home heating systems may use gas, fuel oil or electricity.

An electric heat pump is a versatile climate control unit powered by electricity, capable of both heating and cooling. In summer, a heat pump removes heat from your home's air. In winter, it extracts heat from the outdoor air to warm your home.

When the furnace is on, it burns fuel (gas, oil or electricity) to produce heat, which is then sent through ducts, pipes or wires and emitted via registers, radiators or heating panels.

Older heating systems may heat water to warm the air, using a boiler to store and heat the water supply, which then circulates as hot water through pipes in walls, floors or ceilings.

On the other hand, when an air conditioner is activated, it uses electrical power to cool gas in a coil to a liquid state. This process cools the warm air in your home as it contacts the cooling coil. The cooled air is then directed to different rooms through ducts, or, in the case of room air conditioners, directly from the unit itself.

Once air is warmed or cooled at the heat/cold source, it must be distributed to the various rooms of your home. This can be accomplished with the forced-air, gravity or radiant systems explained below.

A forced-air system distributes the heat produced by the furnace or the coolness produced by a central air conditioner through an electrically powered fan, called a blower, which forces the air through a system of metal ducts to the rooms in your home.

As the warm air from the furnace flows into the rooms, colder air in the rooms flows down through another set of ducts, called the cold-air return system, to the furnace to be warmed.

This system is adjustable: You can increase or decrease the amount of air flowing through your home. Central air-conditioning systems use the same forced-air system, including the blower, to distribute cool air to the rooms and bring warmer air back to be cooled.

Problems with forced-air systems usually involve blower malfunctions. The blower may also be noisy, and it adds the cost of electrical power to the cost of furnace fuel. But because it employs a blower, a forced-air system is an effective way to channel airborne heat or cool air throughout a house.

Gravity systems are based on the principle that hot air rises and cold air sinks. Gravity systems, therefore, cannot be used to distribute cool air from an air conditioner.

In a gravity system, the furnace is located near or below the floor. The warmed air rises and flows through ducts to registers in the floor throughout the house.

If the furnace is located on the main floor of the house, the heat registers are usually positioned high on the walls because the registers must always be higher than the furnace. The warmed air rises toward the ceiling.

As the air cools, it sinks, enters the return air ducts and flows back to the furnace to be reheated.

Another basic distribution system for heating is the radiant system. The heat source is usually hot water, which is heated by the furnace and circulated through pipes embedded in the wall, floor or ceiling.

Radiant systems function by warming the walls, floors or ceilings of rooms or, more commonly, by warming radiators in the rooms. These objects then warm the air in the room.

Some systems use electric heating panels to generate heat, which is radiated into rooms. Like gravity wall heaters, these panels are usually installed in warm climates or where electricity is relatively inexpensive. Radiant systems cannot be used to distribute cool air from an air conditioner.

Radiators and convectors — the most common means of radiant heat distribution in older homes — are used with hot water heating systems. These systems may depend on gravity or on a circulator pump to circulate heated water from the boiler to the radiators or convectors.

A system that uses a pump, or circulator, is called a hydronic system.

Modern radiant heating systems are often built into houses constructed on a concrete slab foundation. A network of hot water pipes is laid under the surface of the concrete slab.

When the concrete is warmed by the pipes, it warms the air that contacts the floor surface. The slab need not get very hot; it will eventually contact and heat the air throughout the house.

Older radiant systems — especially when they depend on gravity — are prone to several problems. The pipes used to distribute the heated water can become clogged with mineral deposits or become slanted at the wrong angle. The boiler in which water is heated at the heat source may also malfunction.

However, modern radiant heating systems typically use circulator pumps and are designed to minimize such issues.

The thermostat, a heat-sensitive switch, is the basic control that regulates the temperature of your home. It responds to changes in the temperature of the air where it is located and turns the furnace or air conditioner on or off as needed to maintain the temperature at a set level, called the set point.

The key component of the thermostat is a bimetallic element that expands or contracts as the temperature increases or decreases in a house.

Older thermostats have two exposed contacts. As the temperature drops, a bimetallic strip bends, making first one electrical contact and then another. The system is fully activated when the second contact closes, turning on the heating system and the anticipator on the thermostat.

The anticipator heats the bimetallic element, causing it to bend and break the second electrical contact. The first contact is not yet broken, however, and the heater keeps running until the temperature rises above the setting on the thermostat.

More modern thermostats have coiled bimetallic strip elements, and the contacts are sealed behind glass to protect them from dirt. As the temperature drops, the bimetallic elements start to uncoil.

The force exerted by the uncoiling of the elements separates a stationary steel bar from a magnet at the end of the coil. The magnet comes down close to the glass-enclosed contact, pulls up on the contact arm inside the tube, and causes the contacts to close, completing the electrical circuit and turning on the heater and the anticipator.

As the air in the room heats up, the coil starts to rewind and breaks the hold of the magnet on the contact arm. The arm drops, breaks the circuit and turns off the system.

As this point, the magnet moves back up to the stationary bar, keeping the contacts open and the heater turned off until the room cools down again.

The latest heat and air-conditioning controls use solid-state electronics for controlling the air temperature. They are typically more accurate and more responsive than older systems. However, repair to solid-state controls usually means replacement.

This article was updated in conjunction with AI technology, then fact-checked and edited by a HowStuffWorks editor.

Electric Furnace Heating Element Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article: